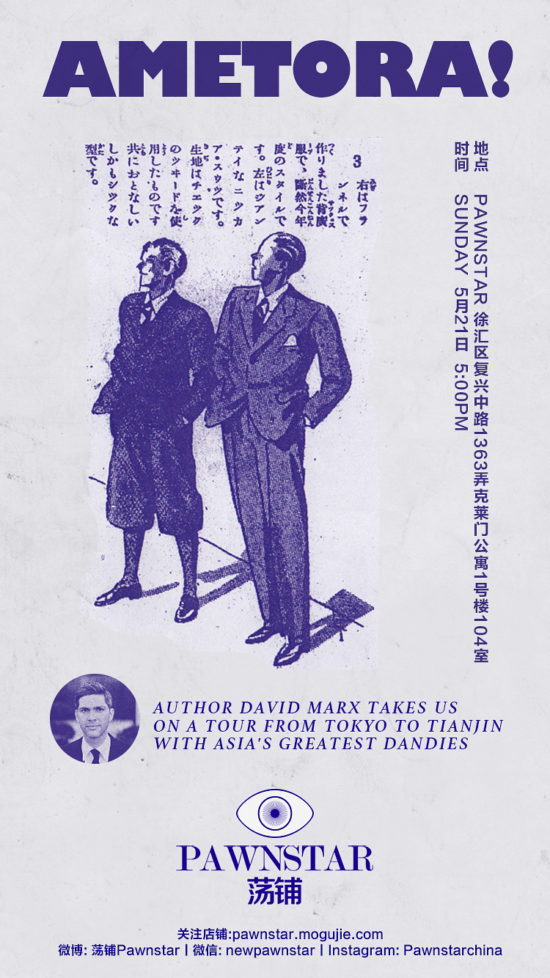

The Ametora event with David Marx that we mentioned before has now been rescheduled and will now be occurring on May 21 at Pawnstar on 1363 Fuxing Middle Road.

Here are some of my thoughts about this event:

China and Japan have had different encounters with Western fashion. That’s not to say that there are more differences than similarities but, when we consider how related these two cultures are, the vastly contrasting experiences with modernity and the West seem poignant. Without delving too much into this, let us just say that the Japanese experience of things Western commenced rather suddenly and with great intensity when in 1870 the Meiji emperor cut his hair short and adopted European-inspired military attire. The next period of great Western influence came with the American occupation. China has interacted with Western styles in its own ways but none matches the sometimes tumultuous but usually rather dedicated love affair the Japanese have had with American style, especially since the 1950s.

In his book, Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style, David Marx tells this story in great detail. We are very lucky that the Tokyo-based American author will be coming through our shop in the Clement Apartments this Sunday (May 21). He will bring to life the stories of young Japanese dandies hiding their love of Ivy League style from their parents and often the government, but secretly promenading on the Ginza by night in seersucker, kakis, repp ties, and all the elements they understood to be Ivy League style. He will tell of the rakish leaders of this movement like Kensuke Ishizu, who was based in Tianjin during the war.

It’s only appropriate that David Marx goes into extreme depth when discussing the Japanese fascination with style. Their interest was always highly detailed and technical, meticulous and studied about how to be unstudied but not seeming deliberately unstudied. They wanted to get every aspect of the style right and, in the process, they made it their own. While the Chinese tend to be more relaxed and march to their own beat when adopting foreign fashions, the Japanese really want to get it all exactly right – more right than the original. That’s how they leave their mark on these styles. Now, even something as gigantic as Uniqlo with its over 1,500 stores in eighteen countries can trace its origins back to the Japanese version of preppy.

Pawnstar has brought David because the Japanese interest in American fashion is an inherently interesting story, but also because there is a sort of moral lesson that seems relevant for a secondhand store to be teaching. “Japanese students in the late 1950s had little pocket money, but Ivy clothing would be a good investment—durable, functional, and based on static, traditional styles,” says Marx.

“And there was something chic about how Ivy students wore items until they disintegrated—holes in shoes, frayed collars on shirts, patches on jacket elbows. Many nouveau riche Japanese would gasp in horror at this frugality, but the old-money Ishizu saw an immediate link between Ivy League fashion and the rakish, rough look of hei’i habÅ, the early twentieth-century phenomenon of elite students flaunting prestige through shabby uniforms.”

Ivy League style was good for Japan in the austere post-war years. It was something sustainable because it wouldn’t go out of style and the items were high quality. These days, we have the opposite situation and can buy as much cheap fashion as we can fit in our wardrobes and then some. Fashion is cheap because the real costs are inflicted upon the environment. They don’t hit our pocket book. But we we thought more about those real costs, we would probably do as the Japanese did then and spend a month’s salary on a good suit that would last a life time – or that could be consigned and bring value for others. It’s this emphasis on quality and enduring style that adds an extra bit of glory to the story of Japan’s encounter with Ivy League style. And of course madras blazers and cordovan loafers are still synonymous with cool.